December 21, 2018 09:52 IST

'China's vulnerability on the global stage has given an opening to India to push for its own interests,' notes Harsh V Pant.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

From Doklam to Wuhan, Sino-Indian relations have taken a great leap in the last year. And it seems more surprises are in the offing.

As the trade war between the US and China escalates, Beijing is reaching out to India in a major way by underscoring the need for the two nations to step up cooperation to fight trade protectionism in the wake of the unilateral approach being adopted by the US on trade-related disputes.

According to the spokesperson of the Chinese embassy in India: 'As the two largest developing countries and major emerging markets, China and India are both in the vital stage of deepening reform and developing economy, and both need stable external environment.'

Using comments by Chinese President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi to safeguard the multilateral trading system and free trade at the World Economic Forum in Davos, it is now being suggested that China and India share common interests in defending the multilateral trading system and free trade and therefore, it is imperative that the two nations work together.

Even as China seems to be panicking, the Donald J Trump administration seems to be in no mood to take the pressure off China.

After imposing tariffs on nearly $200 billion of Chinese imports, President Trump has repeated his threat to slap tariffs on an additional $267 billion of Chinese imports if Beijing pursues a tit-for-tat strategy.

Washington doesn't view China as ready as of yet to reach a deal on trade. 'China wants to make a deal, and I say they're not ready yet,' Mr Trump said.

Trump's latest comments make it clear that Washington is ready to escalate the trade conflict by imposing tariffs on more than $500 billion worth of Chinese goods -- nearly the total amount of US imports from China last year.

At a time when protectionist tendencies in the West are growing by the day, the need for India and China to work together in global governance has been repeatedly highlighted by China in recent months.

At the Wuhan summit, the Chinese president argued: 'As the two largest developing countries and emerging-market economies with a population level of more than one billion, China and India are the backbone of the world's multi-polarisation and economic globalisation.'

Xi underscored the importance of building an open and pluralist global economic order in which all countries can freely participate to pursue their development, while also contributing to the elimination of poverty and inequality in all regions of the world.

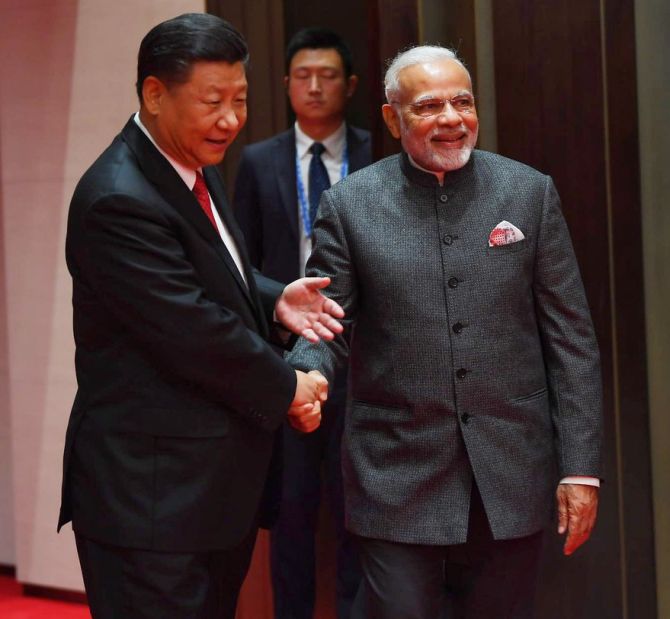

IMAGE: Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi and China's Supreme Leader Xi Jinping at their meeting in Qingdao, China, June 9, 2018. Photograph: Press Information Bureau

The idea that India and China share convergent interests on the global stage and so need to work together is not new.

Throughout the early 1990s, it was this idea on which the broader Sino-Indian partnership was predicated upon.

In fact, the Russia-India-China trilateral arrangement and the BRICS platform evolved out of this synergy.

India and China spoke in one voice against Western interventionist policies in the 1990s and stood up against the West in global trade and climate change negotiations.

It is recently that this engagement has been weakening partly because Beijing seemed keener on reaching bilateral understanding with major Western powers without taking New Delhi into account.

If today China is once again talking about working together with India on global economic issues, there seems to be a realisation in Beijing that Western opinion is turning against it rather rapidly.

China would need partners which can help it alleviate some of these challenges. Its traditional partner of choice, Russia, won't be of much help as it not only is not fully integrated into the global economic order, but has also burned its bridges with the West.

India, meanwhile, remains an emerging economic power both with the heft and credibility to shape the global economic architecture in partnership with the West.

And New Delhi has shown an ability to maintain good relations with major powers, as was exemplified by the Indian decision to go ahead with the signing of the S-400 deal with Russia despite threats of American sanctions.

Key bilateral differences continue to plague the Sino-Indian relationship.

Structural factors that have determined the trajectory of this relationship for the past two decades continue to be influential and are not going to disappear overnight.

What is equally clear is that the top leadership in both countries is cognisant of the challenges that bedevil their relationship and would like to stabilise their relations.

After standing up to the Chinese border adventurism on Doklam last year and by taking a principled but consistent position on the China Pakistan Economic Corridor, India made it clear to China that it will not succumb to brute Chinese power.

India's stature is growing in Chinese eyes. At a time when China is getting isolated in the West and is facing pushback on its flagship Belt and Road Initiative across the world, engagement with India is a key priority for most nations.

This is certainly a moment for New Delhi to tap into and use this opportunity to its fullest.

China's vulnerability on the global stage has given an opening to India to push for its own interests.

China will have to demonstrate its good faith by undertaking a real change in its policies vis-a-vis India before it can expect New Delhi to help it in overcoming its global isolation.

India should respond to Chinese overtures only if China is able to demonstrate a real intent of moving forward on issues that continue to bedevil the bilateral relationship.

Otherwise, the recent Sino-Indian bonhomie would have little meaning beyond generating some headlines.

Harsh V Pant is professor of international relations, department of defence studies, King's College London.

Harsh V Pant

No comments:

Post a Comment