NEW DELHI : Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it," goes the saying. Government policy for India’s telecom sector over the past 25 years has left much to be desired. Not only have mistakes been repeated, but the industry has also had to grapple with various flip-flops in policy.

The upshot: exactly two decades after the government’s relief package for the industry through the New Telecom Policy of 1999, the present government is considering another relief package for the industry. Besides, from the looks of it, Indian telecom seems headed towards a duopoly market again, which is ironic given that this is how it all began for the industry.

THE FIRST CRISIS

Back in 1994, when the P.V. Narasimha Rao government opened the doors for private companies to offer cellular mobile services, it restricted licences to two in each service area. The market, as was envisaged then, was duopoly by design. The companies who won the initial licences were selected through a Beauty Parade, which evaluated aspiring telecom companies on technical and financial parameters. But those who came out shining through this process soon found that subscriber numbers, as well as usage by customers, were nowhere near what they had anticipated.

As a result, the fixed licence fee they had agreed to pay the government was found to be excessively high in hindsight. Representations were made through the Cellular Operators Association of India (COAI) for a relief package, not unlike the situation at present. Besides, the government was taken to court by a number of licence holders because of unrealistic calculations of the revenue potential of a licence.

THE WAY OUT

The government eventually acquiesced and put out the New Telecom Policy in 1999. Companies were offered a so-called migration package, where they were allowed to clear licence fee dues up to 1999 and move to a revenue-sharing model with the government for the remaining period of the licence.

In effect, the government became a stakeholder in the business.

“It was as much a policy change as it was a settlement. There was give and take on both sides and all litigation was withdrawn. As a result, the government also got a piece of the bargain as it did not have to worry about court cases anymore," said Mahesh Uppal, director at communications consulting firm Com First India. After moving to a revenue-sharing arrangement, operators’ revenues gradually but surely improved. After running losses for a number of years, Bharti Airtel Ltd, then known as Bharti Tele-Ventures Ltd, reported marginal earnings before interest and tax (Ebit) of ₹97 crore in fiscal year 2002-03 (FY03). There was no stopping the industry in the next few years. In the next five years, i.e. in FY08, Airtel’s Ebit jumped to ₹4,790 crore, generating a handsome 32% return on capital employed, or ROCE.

In terms of ROCE, FY08 was the peak for the industry leader. The boom, as it turns out, was too good to last.

THE NEXT CRISIS LOOMS

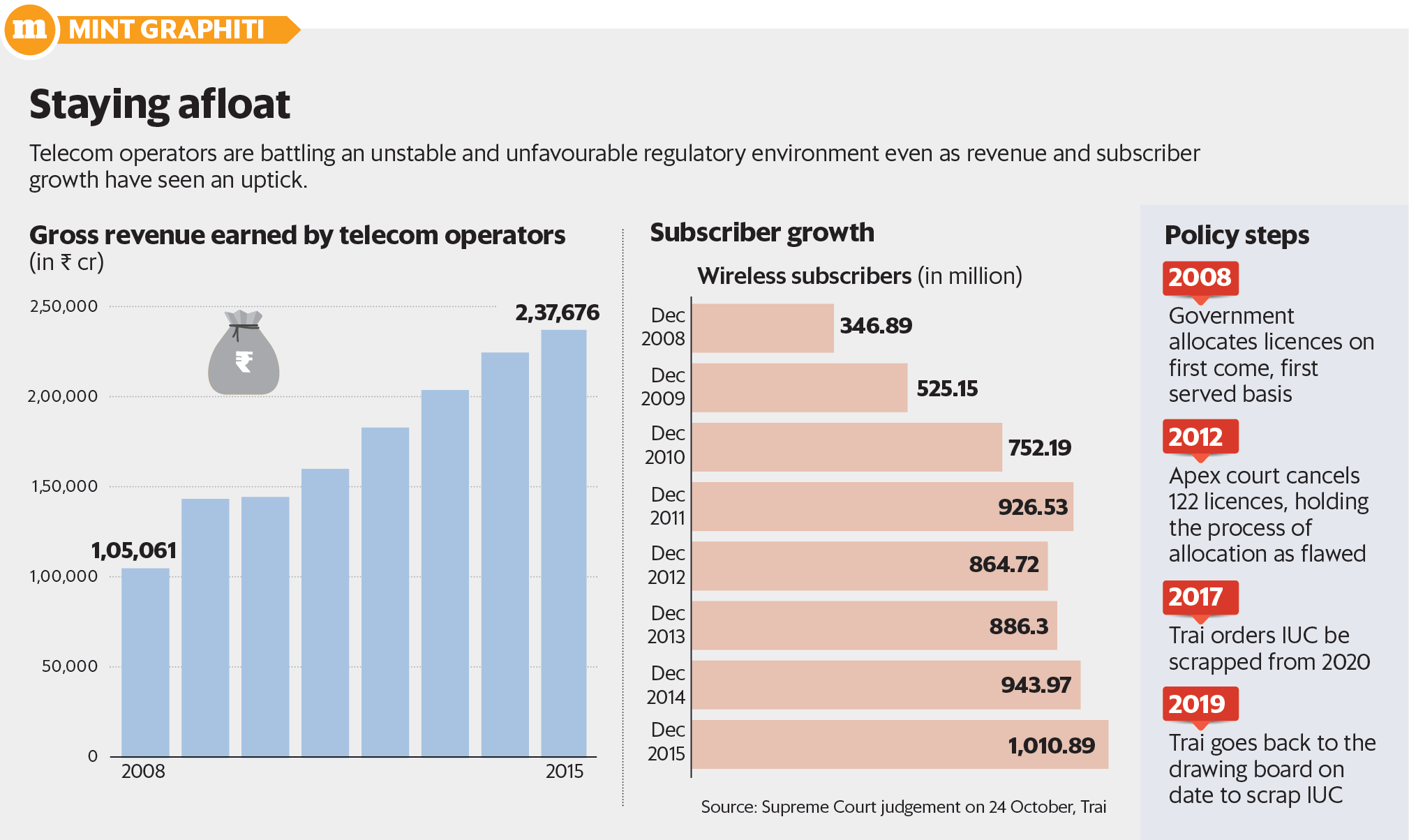

In 2008, during A. Raja’s tenure as telecom minister, 2G spectrum and licences were awarded on a first-come, first-served basis to operators, at a price discovered in an auction held seven years earlier. Overnight, the telecom policy of the country was changed from one that supported limited competition to one of unbridled competition.

A report submitted by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India said 2G licences were issued to telecom operators at throwaway prices, causing a presumptive loss of ₹1.76 trillion to the exchequer. Eventually, the Supreme Court in 2012 cancelled 122 telecom licences and the associated spectrum allocated in 2008, holding that the process of allocation was flawed. The court further directed that spectrum or any natural resource must be auctioned. This sowed the seeds for the gradual shift in the industry structure back to an oligopoly, with worries now that there would soon be a duopoly, with Reliance Jio and Bharti Airtel expected to be the last men standing.

While the government had little choice but to comply with the Supreme Court order, its future course of actions does show that it has to take a fair share of the blame for the current state of the industry.

Apart from dealing a political blow to the then Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government, the sector too went into a tailspin after the Supreme Court order was implemented. Licensees went bankrupt, leading to thousands of jobs being lost. Consumer service quality was also impacted as investment in the sector dried up. India’s reputation as a place to do business suffered immensely. To add to it, this period also saw the government enacting a retrospective tax rule to recover what it thought was its rightful share of profit from Hutchison’s sale of its stake in its India operations to Vodafone Group Plc.

GOOSE THAT LAYS GOLDEN EGGS

While in 2008 the government encouraged unbridled competition, in 2012, it did the exact opposite by recommending a near 10-fold increase in spectrum prices. The government was effectively calling for consolidation in the industry, a move that encouraged the shift towards an oligopolistic structure. With only a few companies in a position to make bids for the expensive spectrum, the decline of relatively smaller companies became swifter. Companies such as Tata Teleservices and Reliance Communications were not small by any stretch of the imagination, but even they couldn’t withstand the pressure that came from high capital investment requirements.

Even for the companies that managed to survive, the hike in spectrum prices was a double whammy. With the New Telecom Policy (NTP) 1999, companies agreed to a revenue share and spectrum was administratively allocated. But now, they needed to bid high amounts for the spectrum just to hold on to existing licences, and also had to continue paying a revenue share. “It was a double levy of sorts," says a former Trai official.

THE FINAL BLOW

Even as operators were reeling under the effects of this major shift in policy, the next big shock hit them when Mukesh Ambani’s new telecom venture Reliance Jio Infocomm Ltd entered the market in September 2016.

Jio disrupted the market with free data and voice offerings, leading to a brutal consolidation that reshaped the entire telecom sector. Companies that were already saddled with debt, due to expensive airwaves bought in previous spectrum auctions, could not compete with the cut-throat tariffs offered by Jio.

Bharti Airtel’s earnings before interest and tax stood at ₹4,928 crore in the year ended 31 March, slightly higher than the ₹4,790 crore Ebit it reported 12 years ago in FY07. But here’s the nub: Since then, the company’s balance sheet size has expanded by 14 times to ₹2.42 trillion. As a result, its current ROCE stands at around 2%, compared to as much as 32% in FY07.

The poor returns of the sector for most of its history has sunk many a large company, even those controlled by large Indian conglomerates such as the Tatas as well as well-known overseas telcos such as UAE’s Etisalat, Russia’s MTS, Japan’s Docomo and Norway’s Telenor.

Bigger legacy operators such as Aircel and Reliance Communications which enjoyed healthy revenue streams on voice calls were suddenly forced to compete with near-free services and eventually went bankrupt. Other smaller operators such as Telenor and Tata Teleservices, unable to survive the cut-throat environment sold their businesses to Bharti Airtel.

With the regulator slashing interconnect usage charges from 14 paise to 6 paise a minute, Jio’s costs on delivering voice calls to rival networks also came down even as it maintained pressure on the market with cheap tariffs. Meanwhile, two large operators—Vodafone India and Idea Cellular decided to merge their pan-India networks to get a fighting chance for survival. However, the merged company and its arch-rival Airtel have been dealt a body-blow after the recent Supreme Court verdict upheld the Union government’s definition of revenue, which requires these telcos to pay past dues to the government.

Bharti Airtel’s dues are roughly ₹21,682 crore, while Vodafone Idea will need to cough up at least ₹28,309 crore. In contrast, Jio’s dues are just ₹13 crore.

There is no other private operator left in the sector and the lack of government intervention at this stage could risk India’s telecom market becoming a duopoly yet again.

Considering the vast amounts that have been invested in the sector over the years, telecom should ideally have been positioned as a shining example of the government’s enabling investment and industry policies. Instead, it has turned out to be a graveyard of sorts for many companies. With the industry having been brought to its knees, it’s hardly surprising that a relatively late entrant, Reliance Jio has, within just three years of its launch, gained market leadership, and looks set to achieve its target of over 50% market share.

For nearly every other company that won a license, India’s telecom industry has been a case of unfulfilled potential, right from the first licence winners in the Beauty Parade.

No comments:

Post a Comment