“KPMG/BSR clearly know who they can take liberties with, and who not, and, clearly, how. In "Silver Blaze", Sherlock Holmes draws attention to the curious incident of the dog in the night. The abuse of the justice system to generate (useful, to the wrongdoer) delay is commonplace. But what is the signal when a watchdog (seemingly) acquiesces in this delay?” Sridharan wondered.

The jurisprudence of audit regulation

US regulator PCAOB has been the pioneer in audit regulation.

The same approach as that of the PCAOB, barring a few details, has been built into the International Audit and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) Standards of Auditing (SoA). The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India adopted the IAASB SoA virtually verbatim, and these now have statutory basis in India as they have been built into the rules issued under the Companies Act, 2013 (CA).

The SoA mandates specific actions by the auditors. These are now statutory duties cast on the auditors under the CA. Non-compliance with the SoA is professional misconduct. This position has been laid down with zero ambiguity even by the ICAI.

Though case law on audit regulation is yet to come up in India, there are judgements on other laws which clearly lay down that non-compliance with any statutory duty is misconduct.

As per the SoA, and therefore under the law, the only acceptable evidence of compliance, or adequate proof of non-compliance, with the mandatory procedures, is the evidence recorded in the audit file as and when the procedures are performed.

For this reason, the audit file acquires great sanctity. As a corollary, nailing down an auditor is relatively an easy job. The audit file does all that is required. With this framework of law, auditors caught for non-compliance can very easily understand that their situation would be hopeless.

An analogy would be of a burglary caught fully on video, with several unimpeachable witnesses to the whole operation. This is why they are keen to settle. Over 90% of all orders passed by the PCAOB, since its inception in 2002, have been settlement orders.

“It helps that the US has a justice system that is ruthlessly efficient, and extremely severe, in the punishments that it deals out (compared to India's). You can take chances with this system only at unacceptably high levels of risk,” Sridharan says.

Corporate law experts agree.

Murali Neelkantan, principal, Amicus says companies will settle only when they perceive a real threat of a higher penalty imposed after adjudication that can be avoided by the settlement. “In the Indian regulatory and judicial system, it seems like there is little chance that there will be any regulatory penalties in the short term. And even when the regulator does occasionally impose penalties, the order will be appealed”.

Typically, courts and tribunals routinely grant a stay on recovery of those penalties and often even overturn the decision of the regulator.

Neelkantan adds, “You only have to look at the number of

Sebi orders that are overturned by SAT after many years and the many more which have been stayed for years on end. Even when SAT does confirm the penalty, there are appeals that can take many years”. It is therefore an incentive for companies to use the slow judicial system to their benefit and take their chances rather than pay any penalties.

Neelkantan points out that the only time there have been settlements with Sebi is when the cost of litigation is likely to be significantly more than the settlement amounts. “How much of the penalties ordered by the Competition Commission of India in the last 20 years have been paid?,” he asks rhetorically.

If there is a quick and effective enforcement of the law there will be an incentive for companies to settle rather than litigate, say experts.

J Sundharesan, a board strategist and compliance expert also feels much is wrong with our courts system. “We have seen over the last 70 years or so whenever there is a problem it is referred to the courts. Even when we know that the justice delivery system is much delayed than in developed countries. What we need is speedy delivery of justice through fast-track company related courts, so that people do not take cover under the legal cases.”

Also, regulators need to identify capable hands internally for faster delivery of justice. “Sometimes the right cases go to the wrong person (which delays the delivery system),” adds Sundharesan.

There are numerous instances over the years where foreign firms operating in India seem to take the country’s laws and institutions lightly.

Some examples are Union Carbide in the Bhopal gas leak case, Citibank and others in the 1992 securities scam, and the Big Four accounting firms in Satyam and IL&FS matters.

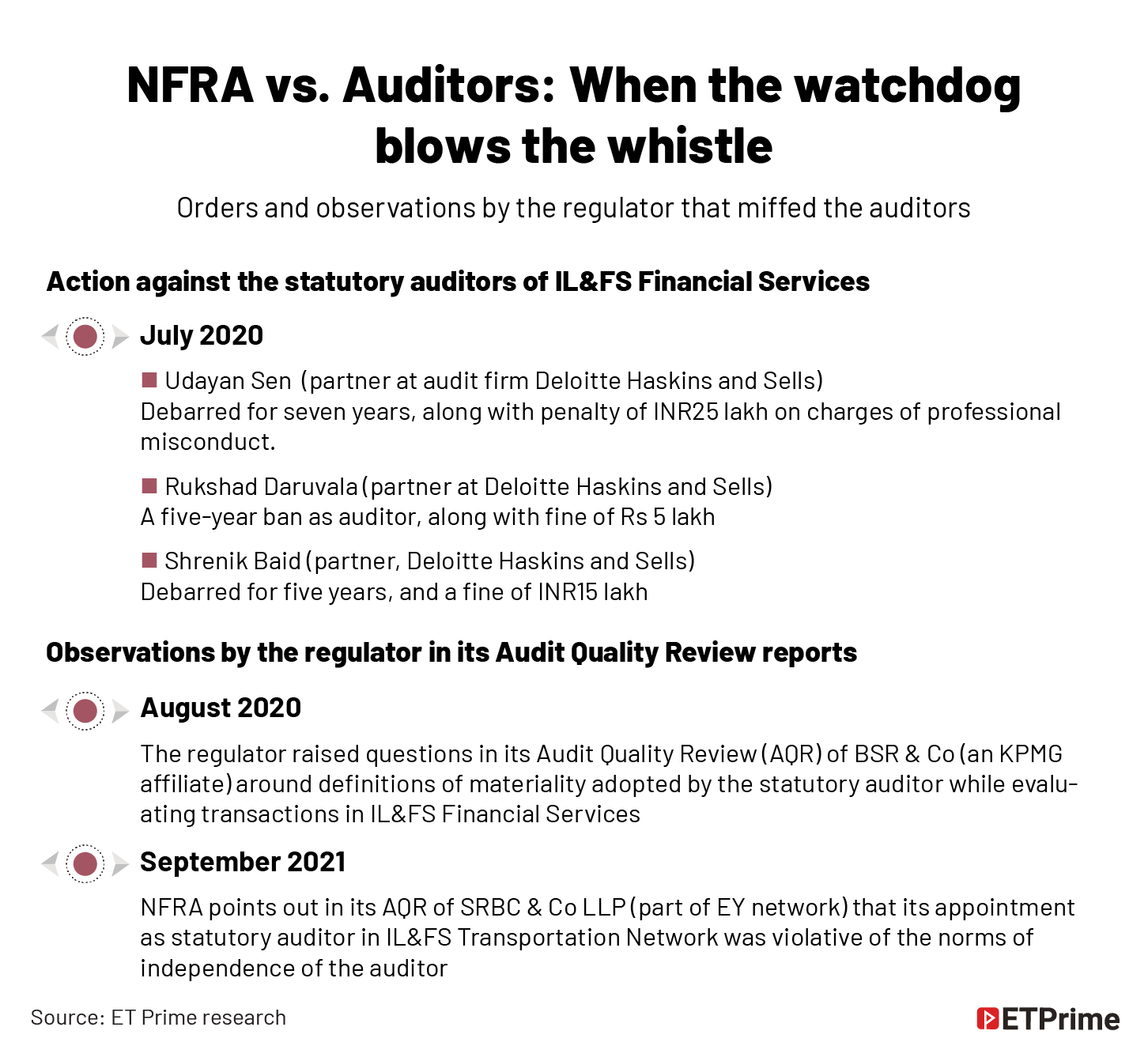

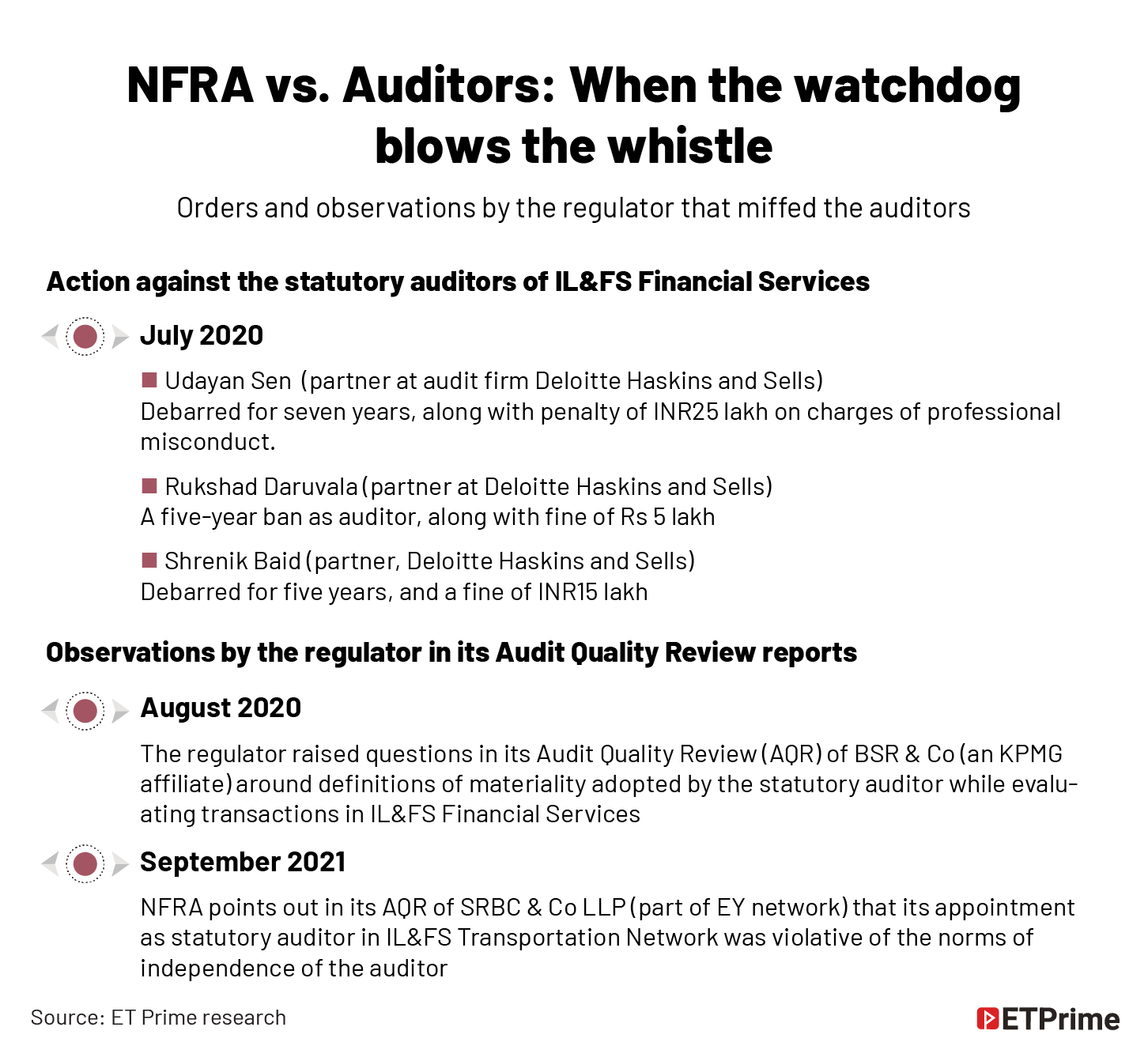

In the IL&FS cases, both

Deloitte and EY network firms and their partner firms have moved court on the issue of jurisprudence questioning the constitutional validity of the NFRA legislation.

Both KPMG and Deloitte have spent millions in settlements in the UK for lapses in the audit of troubled companies. According to a recent report in The Guardian, KPMG reached a GBP14.4 million settlement with the accounting regulator the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) last May, after former staff were accused of forging documents and misleading the regulator over audits for companies that included Carillion.

It came after a tribunal upheld allegations that KPMG and former staff created false meeting minutes and retroactively edited spreadsheets, before sharing those documents with the FRC.

The penalty was one of the largest for a UK auditor, second only to the GBP15 million fine issued to Deloitte in 2020 over its historic audits of the software company Autonomy, The Guardian report said.

Will a settlement mechanism be effective?

The Technical Advisory Committee of the NFRA had suggested that the NFRA should explore the possibility of bringing a settlement mechanism in India. However, NFRA took a view that the ecosystem is not conducive to give enough bite to such a system.

Professor R Narayanaswamy, who headed the TAC till December told ET Prime, “Take the conduct of PwC in Satyam in India and in the US. The PwC settles the matter quietly in the US by paying significant amounts to settle the case with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the PCAOB).

Again, KPMG India settled with the PCAOB for an egregious, even when

judged by Indian practices, violation of auditing requirements in a recent case but it disputes the findings in NFRA’s audit quality reviews in courts instead of going to the appellate tribunal.”

According to Narayanaswamy, there could be several reasons for foreign firms responding differently to actions by the authorities in India from those in their home jurisdictions. “First, enforcement of laws in India is mostly weak and uncertain. Often, the authorities don’t care to act quickly and they mostly blunder when they do act. Second, it takes years for the actions to wind their way through the courts and tribunals because of the slow judicial processes. Finally, there’s a capacity problem because the Indian authorities mostly lack the technical and human resources of the requisite quality to understand a matter and decide on what to do.”

Narayanaswamy recalled having seen the FIR (first information report) filed by the police authorities in an accounting fraud case, and it was impossible to understand what the matter is all about.

He says, “The police are not trained well to investigate white-collar crime with the result the charges are poorly drafted, the section numbers are wrongly mentioned, and the process of collecting and presenting evidence is deeply flawed. The charges are then easily dismissed by the courts. In contrast, the indictments filed by investigators in the US and the UK are drafted rigorously and are intended to stand judicial scrutiny. The documentation by the authorities in India doesn’t come across as professional or earnest. Given all of these, all it takes for anyone is to game the system and get stay after stay from courts.”

Narayanaswamy says that there’s no effective class action by shareholders or lenders in India. “The Companies Act, 2013 has a provision for class action but I don’t know of any case in which it has been invoked.”

Not just the foreign firms

It is not just the foreign firms, even the local audit firms take liberties with the legal system. ET Prime had documented the cat and mouse game

NFRA had to engage with Chaturvedi and Shah, in what appeared to be an open and shut case in the matter of audit of DHFL, another troubled company.

The matter continues to remain in courts and NFRA is yet to pass any order in the matter more than 18 months after this report.

The matter of jurisdiction of NFRA over auditors is a key point of contention in this matter also, where the next hearing is likely to happen in March. This creates the impression that the matter needs to be addressed in totality and NFRA’s hands need further strengthening.

Vijay Kapur, former director, ICAI concedes that the regulatory infrastructure (for auditors) has always been very poor. It was largely ICAI that was responsible for regulation till 2013. Though the concept of an independent regulator was mooted in Companies Act in 2013, it was only in 2018 that the NFRA started its operations. "The process of investigating and penalising auditors has always been very tortuous, procedural, and time-consuming," he says.

Experts agree that though the NFRA has come into the picture over the last four years or so, it has not been allocated any meaningful resources. "In today’s environment you cannot be an effective regulator if you do not have the best of talent and technology available with you. There is also a basic problem in the way our regulators are even staffed," adds Kapur.

Experts feel NFRA needs a big push.They need to be strengthened in terms of resources — technical, talent and financial resources. And then, they have to deliver. Auditors have also tended to take advantage of the turf war between the two regulators.

What do the audit firms say

NFRA and KPMG did not comment on e-mailed queries.

Audit firms take the position that comparison of the two cases and two regimes are unfair as there are numerous differences. According to them, NFRA is a young regulator which needs to mature and stand the test of judicial scrutiny. They also feel that without any settlement mechanism available under the NFRA regime, it would be unfair to compare settlements in the US and the UK with judicial challenges in India.

They also point to the fact that the courts have not dismissed the petitions and therefore taking a view on this sub-judice matter would amount to second guessing the wisdom of the judges.

Ajay Bahl, co-founder & managing partner, AZB & Partners, says, “The suggestion that Indian chartered accountants and firms are getting into frivolous litigation with the regulator is completely incorrect and based on misunderstanding what the issues are, and why they are defending their position.”

Bahl, a CA himself, adds, “The present issues that are sub-judice are what we believe are important questions of law which need to be decided and courts will give the right answer after examining the matter.”

Bahl also feels The comparison between PCAOB and NFRA is unfair as circumstances are different. “There cannot be a wholesale comparison of the PCAOB regime versus NFRA. There are key differences as to how PCAOB reports are written, from how NFRA reports were written, particularly in the past. You cannot create a comparison of regimes and super impose outcomes of one on the other or judge which is better as they are two different regimes/processes. Overall NFRA will have a positive effect on the upliftment of the standard of financial reporting. The change can come through a mixture of indictment, threat of indictment and dialogue.”

Sridharan cites the Kingman Review on the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) — accounting body for the UK. In 2018, John Kingman, a former banker and bureaucrat, was asked by the government to undertake a critical review of the FRC. He recommended that the FRC should be replaced by a new body which, among other things, "is respected by those who depend on its work, and where necessary feared by those whom it regulates".

If NFRA has to attain such a status, clarity on the law is absolutely essential. It will be the prayer of various stakeholders in the work done by these audit firms that the courts will oblige soon.

(Graphics by Sadhana Saxena)

“KPMG/BSR clearly know who they can take liberties with, and who not, and, clearly, how. In "Silver Blaze", Sherlock Holmes draws attention to the curious incident of the dog in the night. The abuse of the justice system to generate (useful, to the wrongdoer) delay is commonplace. But what is the signal when a watchdog (seemingly) acquiesces in this delay?” Sridharan wondered.

The jurisprudence of audit regulation

US regulator PCAOB has been the pioneer in audit regulation.

The same approach as that of the PCAOB, barring a few details, has been built into the International Audit and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) Standards of Auditing (SoA). The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India adopted the IAASB SoA virtually verbatim, and these now have statutory basis in India as they have been built into the rules issued under the Companies Act, 2013 (CA).

The SoA mandates specific actions by the auditors. These are now statutory duties cast on the auditors under the CA. Non-compliance with the SoA is professional misconduct. This position has been laid down with zero ambiguity even by the ICAI.

Though case law on audit regulation is yet to come up in India, there are judgements on other laws which clearly lay down that non-compliance with any statutory duty is misconduct.

As per the SoA, and therefore under the law, the only acceptable evidence of compliance, or adequate proof of non-compliance, with the mandatory procedures, is the evidence recorded in the audit file as and when the procedures are performed.

For this reason, the audit file acquires great sanctity. As a corollary, nailing down an auditor is relatively an easy job. The audit file does all that is required. With this framework of law, auditors caught for non-compliance can very easily understand that their situation would be hopeless.

An analogy would be of a burglary caught fully on video, with several unimpeachable witnesses to the whole operation. This is why they are keen to settle. Over 90% of all orders passed by the PCAOB, since its inception in 2002, have been settlement orders.

“It helps that the US has a justice system that is ruthlessly efficient, and extremely severe, in the punishments that it deals out (compared to India's). You can take chances with this system only at unacceptably high levels of risk,” Sridharan says.

Corporate law experts agree.

Murali Neelkantan, principal, Amicus says companies will settle only when they perceive a real threat of a higher penalty imposed after adjudication that can be avoided by the settlement. “In the Indian regulatory and judicial system, it seems like there is little chance that there will be any regulatory penalties in the short term. And even when the regulator does occasionally impose penalties, the order will be appealed”.

Typically, courts and tribunals routinely grant a stay on recovery of those penalties and often even overturn the decision of the regulator.

Neelkantan adds, “You only have to look at the number of

Sebi orders that are overturned by SAT after many years and the many more which have been stayed for years on end. Even when SAT does confirm the penalty, there are appeals that can take many years”. It is therefore an incentive for companies to use the slow judicial system to their benefit and take their chances rather than pay any penalties.

Neelkantan points out that the only time there have been settlements with Sebi is when the cost of litigation is likely to be significantly more than the settlement amounts. “How much of the penalties ordered by the Competition Commission of India in the last 20 years have been paid?,” he asks rhetorically.

If there is a quick and effective enforcement of the law there will be an incentive for companies to settle rather than litigate, say experts.

J Sundharesan, a board strategist and compliance expert also feels much is wrong with our courts system. “We have seen over the last 70 years or so whenever there is a problem it is referred to the courts. Even when we know that the justice delivery system is much delayed than in developed countries. What we need is speedy delivery of justice through fast-track company related courts, so that people do not take cover under the legal cases.”

Also, regulators need to identify capable hands internally for faster delivery of justice. “Sometimes the right cases go to the wrong person (which delays the delivery system),” adds Sundharesan.

There are numerous instances over the years where foreign firms operating in India seem to take the country’s laws and institutions lightly.

Some examples are Union Carbide in the Bhopal gas leak case, Citibank and others in the 1992 securities scam, and the Big Four accounting firms in Satyam and IL&FS matters.

In the IL&FS cases, both

Deloitte and EY network firms and their partner firms have moved court on the issue of jurisprudence questioning the constitutional validity of the NFRA legislation.

Both KPMG and Deloitte have spent millions in settlements in the UK for lapses in the audit of troubled companies. According to a recent report in The Guardian, KPMG reached a GBP14.4 million settlement with the accounting regulator the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) last May, after former staff were accused of forging documents and misleading the regulator over audits for companies that included Carillion.

It came after a tribunal upheld allegations that KPMG and former staff created false meeting minutes and retroactively edited spreadsheets, before sharing those documents with the FRC.

The penalty was one of the largest for a UK auditor, second only to the GBP15 million fine issued to Deloitte in 2020 over its historic audits of the software company Autonomy, The Guardian report said.

Will a settlement mechanism be effective?

The Technical Advisory Committee of the NFRA had suggested that the NFRA should explore the possibility of bringing a settlement mechanism in India. However, NFRA took a view that the ecosystem is not conducive to give enough bite to such a system.

Professor R Narayanaswamy, who headed the TAC till December told ET Prime, “Take the conduct of PwC in Satyam in India and in the US. The PwC settles the matter quietly in the US by paying significant amounts to settle the case with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the PCAOB).

Again, KPMG India settled with the PCAOB for an egregious, even when

judged by Indian practices, violation of auditing requirements in a recent case but it disputes the findings in NFRA’s audit quality reviews in courts instead of going to the appellate tribunal.”

According to Narayanaswamy, there could be several reasons for foreign firms responding differently to actions by the authorities in India from those in their home jurisdictions. “First, enforcement of laws in India is mostly weak and uncertain. Often, the authorities don’t care to act quickly and they mostly blunder when they do act. Second, it takes years for the actions to wind their way through the courts and tribunals because of the slow judicial processes. Finally, there’s a capacity problem because the Indian authorities mostly lack the technical and human resources of the requisite quality to understand a matter and decide on what to do.”

Narayanaswamy recalled having seen the FIR (first information report) filed by the police authorities in an accounting fraud case, and it was impossible to understand what the matter is all about.

He says, “The police are not trained well to investigate white-collar crime with the result the charges are poorly drafted, the section numbers are wrongly mentioned, and the process of collecting and presenting evidence is deeply flawed. The charges are then easily dismissed by the courts. In contrast, the indictments filed by investigators in the US and the UK are drafted rigorously and are intended to stand judicial scrutiny. The documentation by the authorities in India doesn’t come across as professional or earnest. Given all of these, all it takes for anyone is to game the system and get stay after stay from courts.”

Narayanaswamy says that there’s no effective class action by shareholders or lenders in India. “The Companies Act, 2013 has a provision for class action but I don’t know of any case in which it has been invoked.”

Not just the foreign firms

It is not just the foreign firms, even the local audit firms take liberties with the legal system. ET Prime had documented the cat and mouse game

NFRA had to engage with Chaturvedi and Shah, in what appeared to be an open and shut case in the matter of audit of DHFL, another troubled company.

The matter continues to remain in courts and NFRA is yet to pass any order in the matter more than 18 months after this report.

The matter of jurisdiction of NFRA over auditors is a key point of contention in this matter also, where the next hearing is likely to happen in March. This creates the impression that the matter needs to be addressed in totality and NFRA’s hands need further strengthening.

Vijay Kapur, former director, ICAI concedes that the regulatory infrastructure (for auditors) has always been very poor. It was largely ICAI that was responsible for regulation till 2013. Though the concept of an independent regulator was mooted in Companies Act in 2013, it was only in 2018 that the NFRA started its operations. "The process of investigating and penalising auditors has always been very tortuous, procedural, and time-consuming," he says.

Experts agree that though the NFRA has come into the picture over the last four years or so, it has not been allocated any meaningful resources. "In today’s environment you cannot be an effective regulator if you do not have the best of talent and technology available with you. There is also a basic problem in the way our regulators are even staffed," adds Kapur.

Experts feel NFRA needs a big push.They need to be strengthened in terms of resources — technical, talent and financial resources. And then, they have to deliver. Auditors have also tended to take advantage of the turf war between the two regulators.

What do the audit firms say

NFRA and KPMG did not comment on e-mailed queries.

Audit firms take the position that comparison of the two cases and two regimes are unfair as there are numerous differences. According to them, NFRA is a young regulator which needs to mature and stand the test of judicial scrutiny. They also feel that without any settlement mechanism available under the NFRA regime, it would be unfair to compare settlements in the US and the UK with judicial challenges in India.

They also point to the fact that the courts have not dismissed the petitions and therefore taking a view on this sub-judice matter would amount to second guessing the wisdom of the judges.

Ajay Bahl, co-founder & managing partner, AZB & Partners, says, “The suggestion that Indian chartered accountants and firms are getting into frivolous litigation with the regulator is completely incorrect and based on misunderstanding what the issues are, and why they are defending their position.”

Bahl, a CA himself, adds, “The present issues that are sub-judice are what we believe are important questions of law which need to be decided and courts will give the right answer after examining the matter.”

Bahl also feels The comparison between PCAOB and NFRA is unfair as circumstances are different. “There cannot be a wholesale comparison of the PCAOB regime versus NFRA. There are key differences as to how PCAOB reports are written, from how NFRA reports were written, particularly in the past. You cannot create a comparison of regimes and super impose outcomes of one on the other or judge which is better as they are two different regimes/processes. Overall NFRA will have a positive effect on the upliftment of the standard of financial reporting. The change can come through a mixture of indictment, threat of indictment and dialogue.”

Sridharan cites the Kingman Review on the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) — accounting body for the UK. In 2018, John Kingman, a former banker and bureaucrat, was asked by the government to undertake a critical review of the FRC. He recommended that the FRC should be replaced by a new body which, among other things, "is respected by those who depend on its work, and where necessary feared by those whom it regulates".

If NFRA has to attain such a status, clarity on the law is absolutely essential. It will be the prayer of various stakeholders in the work done by these audit firms that the courts will oblige soon.

(Graphics by Sadhana Saxena)

No comments:

Post a Comment