Updated:

No coming back

The stranger showed up at the girl's door one night with a tantalizing job offer: Give up your world, and I will give you a future.

It was a chance for 16-year-old Marselina Neonbota to leave her isolated village in one of the poorest parts of Indonesia for neighboring Malaysia, where some migrant workers can earn more in a few years than in a lifetime at home. A way out for a girl so hungry for a life beyond subsistence farming that she walked 22 kilometers (14 miles) every day to the schoolhouse and back.

She grabbed the opportunity _ and disappeared.

The cheerful child known to her family as Lina joined the army of Indonesians who migrate every year to wealthier countries in Asia and the Middle East for work. Thousands come home in coffins, or vanish. Among them, possibly hundreds of trafficked girls have quietly disappeared from the impoverished western half of Timor island and elsewhere in Indonesia's East Nusa Tenggara province.

It was a chance for 16-year-old Marselina Neonbota to leave her isolated village in one of the poorest parts of Indonesia for neighboring Malaysia, where some migrant workers can earn more in a few years than in a lifetime at home. A way out for a girl so hungry for a life beyond subsistence farming that she walked 22 kilometers (14 miles) every day to the schoolhouse and back.

She grabbed the opportunity _ and disappeared.

The cheerful child known to her family as Lina joined the army of Indonesians who migrate every year to wealthier countries in Asia and the Middle East for work. Thousands come home in coffins, or vanish. Among them, possibly hundreds of trafficked girls have quietly disappeared from the impoverished western half of Timor island and elsewhere in Indonesia's East Nusa Tenggara province.

1/8

AP

Blackest of black holes

When it comes to tracking the fate of migrants, Asia is the blackest of black holes.

It has more migrants than any region on earth, with millions traveling within Asia and to the Mideast for work. Yet it has the least data on those who vanish. In an exclusive tally, The Associated Press found more than 8,000 cases of dead and missing migrants in Asia and the Mideast since 2014, in addition to the 2,700 listed by the U.N.'s International Organization for Migration. More than 2,000 unearthed by the AP were from the Philippines alone. And countless other cases are never reported.

These workers reflect part of the hidden toll of global migration. An AP investigation documented at least 61,135 migrants dead or missing worldwide over the same period, a tally that keeps rising . That's more than double the number found by the IOM, the only group that has tried to count them.

While it's not clear how many left for jobs, in general workers make up about two-thirds of international migrants, according to the International Labor Organization; the rest are fleeing everything from drug violence to war and famine. Migrants may die on perilous journeys through deserts or at sea, while many others like Lina disappear into networks that traffic in people.

It has more migrants than any region on earth, with millions traveling within Asia and to the Mideast for work. Yet it has the least data on those who vanish. In an exclusive tally, The Associated Press found more than 8,000 cases of dead and missing migrants in Asia and the Mideast since 2014, in addition to the 2,700 listed by the U.N.'s International Organization for Migration. More than 2,000 unearthed by the AP were from the Philippines alone. And countless other cases are never reported.

These workers reflect part of the hidden toll of global migration. An AP investigation documented at least 61,135 migrants dead or missing worldwide over the same period, a tally that keeps rising . That's more than double the number found by the IOM, the only group that has tried to count them.

While it's not clear how many left for jobs, in general workers make up about two-thirds of international migrants, according to the International Labor Organization; the rest are fleeing everything from drug violence to war and famine. Migrants may die on perilous journeys through deserts or at sea, while many others like Lina disappear into networks that traffic in people.

2/8

AP

Illegal recruitment turned trafficking

The National Agency for Placement and Protection of Indonesian Workers has counted more than 2,600 cases of dead or missing Indonesian migrants since 2014. And even those numbers mostly leave out people like Lina who are recruited illegally -- an estimated 30 percent of Indonesia's 6.2 million migrant workers.

On that night in 2010, Lina didn't seem to sense the danger posed by the stranger named Sarah. But Lina's great-aunt and great-uncle, who had raised her, were hesitant.

Sarah insisted they could trust her; she was related to the village chief. And Lina would only be gone two years.

Lina's aunt, Teresia Tasoin, knew a Malaysian salary could support the whole family. Her husband _ fighting both a teenager's excitement and a crushing headache _ doubted he could stop Lina from going.

Still, the couple wanted to hold a Catholic prayer service for Lina before she left. Sarah promised she would only take Lina to the provincial capital of Kupang for one night to organize her paperwork, then bring her back the next day. It was a lie.

Less than one hour after Sarah walked into their home, she walked back out with Lina. And just like that, their girl was gone.

Looking back on it now, Tasoin crumbles under the weight of what-ifs. "I regret it,'' she says through tears.

"I regret letting her go.''

On that night in 2010, Lina didn't seem to sense the danger posed by the stranger named Sarah. But Lina's great-aunt and great-uncle, who had raised her, were hesitant.

Sarah insisted they could trust her; she was related to the village chief. And Lina would only be gone two years.

Lina's aunt, Teresia Tasoin, knew a Malaysian salary could support the whole family. Her husband _ fighting both a teenager's excitement and a crushing headache _ doubted he could stop Lina from going.

Still, the couple wanted to hold a Catholic prayer service for Lina before she left. Sarah promised she would only take Lina to the provincial capital of Kupang for one night to organize her paperwork, then bring her back the next day. It was a lie.

Less than one hour after Sarah walked into their home, she walked back out with Lina. And just like that, their girl was gone.

Looking back on it now, Tasoin crumbles under the weight of what-ifs. "I regret it,'' she says through tears.

"I regret letting her go.''

3/8

AP

A matter of family betrayal

Unlike Lina, Orance Faot was betrayed by her own flesh and blood.

The road to her house is so rocky that by the time you arrive, it feels like you've gone through an hours-long earthquake. The sunny, hardworking girl was just 14 when she traveled down that same rocky path four years ago on a motorbike bound for Kupang.

That morning, Orance told the grandmother she lived with, Margarita Oematan, that she was going with her older cousin Yeni to a priest's house to study the Bible. When she failed to return, her uncle went looking for her. He walked as far as the river where she sometimes swam, but found no trace of his niece or Yeni. A driver later told the family that the girls had hired a bike.

When the family finally got hold of Yeni, she denied knowing what had happened to Orance. But the Faots suspected Yeni had turned Orance over to a recruiter. Eventually, they did something few here do _ they went to the police.

The road to her house is so rocky that by the time you arrive, it feels like you've gone through an hours-long earthquake. The sunny, hardworking girl was just 14 when she traveled down that same rocky path four years ago on a motorbike bound for Kupang.

That morning, Orance told the grandmother she lived with, Margarita Oematan, that she was going with her older cousin Yeni to a priest's house to study the Bible. When she failed to return, her uncle went looking for her. He walked as far as the river where she sometimes swam, but found no trace of his niece or Yeni. A driver later told the family that the girls had hired a bike.

When the family finally got hold of Yeni, she denied knowing what had happened to Orance. But the Faots suspected Yeni had turned Orance over to a recruiter. Eventually, they did something few here do _ they went to the police.

4/8

AP

'Homecoming' in a coffin

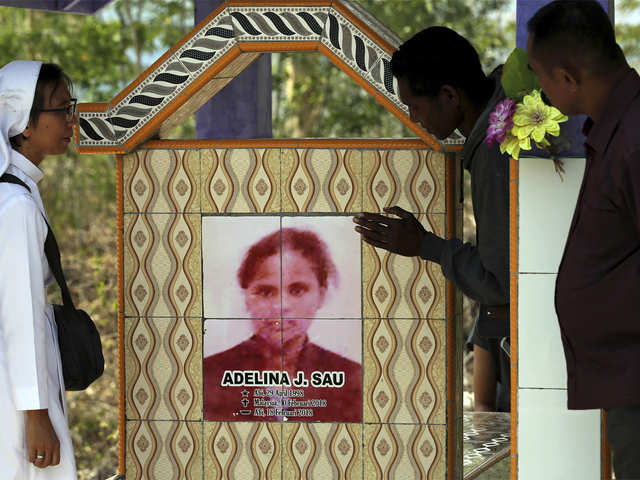

Adelina Sau's long journey home came in a shrink-wrapped coffin marked "Fragile.''

Her grave lies along the side of a lonely road. Staring out from the tombstone's tiles is a blurry picture of her face, an image taken from a photo a cop snapped of her passport.

That grainy picture-of-a-picture is the only photo of Adelina that her family has. A copy hangs on the wall of their tin-roofed house, above a few sacks of rice that will feed the family half the year. The rest of the time, they will survive on their corn and cassava crops.

Her grave lies along the side of a lonely road. Staring out from the tombstone's tiles is a blurry picture of her face, an image taken from a photo a cop snapped of her passport.

That grainy picture-of-a-picture is the only photo of Adelina that her family has. A copy hangs on the wall of their tin-roofed house, above a few sacks of rice that will feed the family half the year. The rest of the time, they will survive on their corn and cassava crops.

5/8

AP

Endless cycle

Gnarled trees cling to barren hills. Many of the rivers have run dry. Emaciated dogs lick desperately at cracked-open coconuts lying on the dusty ground.

With no real industry here, generations of villagers have migrated to Malaysia to work as maids or on plantations. But in the past few years, migrant trafficking has picked up, as traffickers move to the most remote areas in search of fresh, unsuspecting prey. Many victims end up overworked and underpaid, and some are forced into prostitution.

In the village of Oe'Ekam, priest Maximus Amfotis watches as locals line up at a water tank, filling containers some will have to lug several kilometers home. He regularly hears of local teens migrating to Malaysia for work, never to return. There was a new case just two weeks ago, he says. The cycle seems endless.

"If we cannot stop this problem,'' he says, "I fear that the current generation will be lost.''

With no real industry here, generations of villagers have migrated to Malaysia to work as maids or on plantations. But in the past few years, migrant trafficking has picked up, as traffickers move to the most remote areas in search of fresh, unsuspecting prey. Many victims end up overworked and underpaid, and some are forced into prostitution.

In the village of Oe'Ekam, priest Maximus Amfotis watches as locals line up at a water tank, filling containers some will have to lug several kilometers home. He regularly hears of local teens migrating to Malaysia for work, never to return. There was a new case just two weeks ago, he says. The cycle seems endless.

"If we cannot stop this problem,'' he says, "I fear that the current generation will be lost.''

6/8

AP

"Sister Cargo"

In deeply Christian East Nusa Tenggara, the church has become one of the few advocates for the dead and disappeared. With the impoverished province home to the highest number of trafficking cases in the country, nuns and priests have transformed themselves into counter-trafficking crusaders.

Inside a little church across from Lina's house, Sister Laurentina is praying before a riveted crowd. Slight and soft-spoken, the nun _ who like many Indonesians goes by only one name _ is nonetheless a giant presence before the parishioners. There is danger in trusting illegal recruiters, she warns. There is death.

Her words are not hyperbole. She waits at the airport for the arrival of nearly every migrant worker's corpse that is flown back to Kupang, a ritual that has earned her the nickname "Sister Cargo.'' One day after her warning to parishioners, she will be back at the airport, praying over the 89th coffin this year that has returned from Malaysia with the remains of a local migrant. Some die from accidents or illness, she says. Others from neglect and abuse.

Inside a little church across from Lina's house, Sister Laurentina is praying before a riveted crowd. Slight and soft-spoken, the nun _ who like many Indonesians goes by only one name _ is nonetheless a giant presence before the parishioners. There is danger in trusting illegal recruiters, she warns. There is death.

Her words are not hyperbole. She waits at the airport for the arrival of nearly every migrant worker's corpse that is flown back to Kupang, a ritual that has earned her the nickname "Sister Cargo.'' One day after her warning to parishioners, she will be back at the airport, praying over the 89th coffin this year that has returned from Malaysia with the remains of a local migrant. Some die from accidents or illness, she says. Others from neglect and abuse.

7/8

AP

Education cures them all

Laurentina is one of the few people in West Timor even trying to track the missing. Since 2012, she has traveled across the island to educate villagers on the dangers of traffickers. She has held at least 20 meetings this year alone.

Laurentina asks each audience if anyone has lost contact with a relative who migrated for work. And at every meeting, for six years, at least one or two people have told her: Yes, my child is missing. Most are girls.

The remoteness of West Timor and a lack of education mean many people just don't understand the danger. But even for those who do, a trip through the drought-punished region makes clear why they risk their lives to leave.

Laurentina asks each audience if anyone has lost contact with a relative who migrated for work. And at every meeting, for six years, at least one or two people have told her: Yes, my child is missing. Most are girls.

The remoteness of West Timor and a lack of education mean many people just don't understand the danger. But even for those who do, a trip through the drought-punished region makes clear why they risk their lives to leave.

No comments:

Post a Comment